In a nostalgic glimpse at the ’70s, Armenian Museum of Fresno captures a vibrant generation through photos and sound

By Anahid Valencia

The Armenian Museum of Fresno is hidden in the unassuming University of California building across the street from the bustling Fashion Fair mall. Inside are dozens of artifacts, paintings, and thanks to a new exhibition that opened June 25 titled “Fresno Armenians: 50 Years Ago,” over 300 photos capturing the essence of Fresno Armenian events in the 1970s.

Having attended many Armenian-centered events in my life, I knew exactly at the exhibition opening reception what I was walking into: trays and trays of food, a game of backgammon and a warm feeling of community as people gathered around the photos saying things like, “that’s my grandmother,” and “I know him.”

I also figured there would be music, and there was. Composer Joseph Bohigian debuted a series of soulful, ear-tugging sound installations that transported me immediately to the Armenian Highlands.

Robby Antoyan is the photographer behind it all and spent roughly one year attending Armenian picnics, church gatherings and parties in 1975, taking pictures of people only “60 [and] over.”

The Munro Review has no paywall but is financially supported by readers who believe in its non-profit mission of bringing professional arts journalism to the central San Joaquin Valley. You can help by signing up for a monthly recurring paid membership or make a one-time donation of as little as $3. All memberships and donations are tax-deductible. The Munro Review is funded in part by the City of Fresno Measure P Expanded Access to Arts and Culture Fund administered by the Fresno Arts Council.

“Their looks are not gonna stay – their look is gonna die with them,” Antoyan said. “So I thought, ‘I think it’d be kind of nice to be able to take photographs of them in a very natural setting, enjoying themselves.’”

When I arrived at the exhibition, I was eager to search for relatives in the photos (I found some), and I noticed how happy the photographed individuals looked, dressed in their finest Sunday clothes and their hair roller-curled to the sky. However, not long after I truly examined the pictures, I felt a sense of grief creeping up on me.

Though it seemed obvious, Armenian to Armenian, I asked Antoyan why he chose to photograph specifically Armenians in this age range. He explained that it all comes down to the Armenian Genocide, a phrase that seems to echo in the minds of second and third generation Armenians.

“That’s the only reason why they were here,” Antoyan said. “My dad’s family took major hits as well as my mom’s. It’s something that needs to be done, it needs to be not necessarily documented, but it needs to be remembered.”

The memories of 1915, whether passed down by family members or discovered later in life, are embedded into the very essence of the Armenian diaspora. Though Armenians, as the photos suggest, have made one hell of a comeback.

◊ ◊ ◊

Antoyan first picked up a camera during his junior year of college at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo to escape the sometimes stressful nature of education. He began by photographing the beachy scenes near the coast of San Luis Obispo (SLO), and while he was there, Antoyan quickly realized that many people did not know what an Armenian was.

“So I installed some information about Armenians on the wall of my drawing cubicle,” he writes in his biography displayed at the exhibition. “A copy of a map of the world showing where we were and where Armenian was/is, some of its history, a copy of the Armenian alphabet, and a small tricolor flag.”

When Antoyan returned to Fresno, the stark contrast was impossible to ignore. He explained that Armenians were everywhere in Fresno, and since his family was involved in the Armenian church, he became aware of Armenians in all forms. Specifically, the older Armenians who came to America through the genocide.

“There was a unique aura/character on how those older Armenians would just be themselves,” Antoyan said. “I did not notice this until I left to live in SLO.”

Though Antoyan’s photography journey did not begin until college, the idea behind this project had been developing in his mind for years.

“I started this when I was much younger, I started thinking, you know, there’s a lot of people dying that I had no clue of,” he said.

Today, Antoyan’s intention remains the same– to remind those in the present of those in the past.

“These are photographs of friends or family members that they hadn’t seen before, who more than likely aren’t even around anymore,” he said. “This, I think, would be hopefully something of enjoyment for these people.”

◊ ◊ ◊

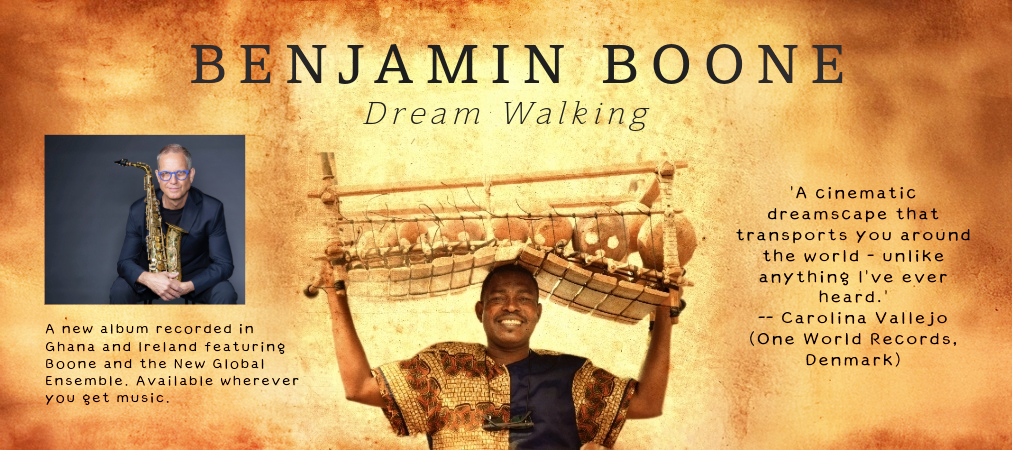

Bohigian is a Fresno native and a Fresno State graduate (studying with Kenneth Froelich and Benjamin Boone) who went on to earn a doctorate in composition from Stony Brook University in New York. His music has been performed in such places as Los Angeles, Yerevan, Melbourne, Ireland and Montreal. He composed his pieces as a way of honoring his family and community members who came to California in escape of the Armenian Genocide, similar to Antoyan. His music installation combines facets of beauty, pain and remembrance into a collection that plays in the background of the exhibition.

Photo by Raffi Paul

Photo by Raffi Paul Composer Joseph Boghigian

The pieces take from many different sources, with one notably being the voice of his great-grandmother, Seranouch, explaining her journey to America. Seranouch’s voice speaks softly along with the eerily beautiful sounds of the Armenian oud.

“I didn’t discover until last year when I started working on this project that there was actually an audio tape, so I really wanted to use that to incorporate her voice,” Bohigian said.

The Armenian word for memory is husher (depending on who spells it). Bohigian explained that this word helped drive him to the Armenian Heritage Museum to debut his creation after speaking with Varoujan Der Simonian, the museum’s director.

“Varoujan approached me about doing a project, something related to memory in Fresno,” Bohigian said. “That’s something that I think about a lot in my music that I compose, and I hadn’t done anything in Fresno for a long time.”

◊ ◊ ◊

The opening reception’s turnout was more than Der Simonian had seen in an estimated seven years at an exhibition. He explained that when something is personal, it draws people in.

“You’re not only showing fine art, you’re not only showing drawings in general, abstract or realistic, but it’s photography of their own people, how they lived,” Der Simonian said. “I think that’s what makes it very successful.”

“You’re not only showing fine art, you’re not only showing drawings in general, abstract or realistic, but it’s photography of their own people, how they lived,” Der Simonian said. “I think that’s what makes it very successful.”

Der Simonian said that the installation will be open to the public until Aug. 27, but the museum will extend the date if there is a high demand.

Until the opening, the individuals in the photos were not named. As attendees looked closer and took a seat in a train to the past, some noticed their family members and told the museum’s management so they could be identified. Attendee Pauline Sahakian found her late brother, John Sahakian, in one picture, playing the Armenian oud alongside two others.

“He had a great sense of humor and a big laugh, and he loved playing the oud,” Sahakian said. “It was just one of those things that that generation [did], you know, you played Armenian music.”

As Sahakian’s face lit up when speaking about her brother, I could hear several others in the room recognizing faces and saying, “Wow, there she is.”

Anahid Valencia is a Fresno State journalism student and news editor of The Collegian, the campus newspaper.