Jack Fortner, 1935-2020: composer, conductor, professor and a wonderfully lived musical life

Jack Fortner knew how to pitch a concert to the media.

I always understood I was in for something interesting — even daring — when I wrote about the eclectic and unpredictable fare offered by the Orpheus chamber ensemble. It wasn’t just the nature of the individual pieces in a given concert. As founding artistic director, Dr. Fortner loved shaping his programs into pieces of art themselves, almost like a sculptor. It’s no surprise to learn, then, that along with everything else in his remarkable life — touring the U.S. as a jazz saxophonist, studying composition at Juilliard, earning his doctorate at the University of Michigan, attaining the rank of professor emeritus at Fresno State, founding Orpheus in 1978, conducting around the world, receiving numerous awards and commissions for his compositions — he studied art in college.

Pictured above: Dr. Jack Fortner as a young musician; conducting the Camará Ensemble in Brazil; with his wife, Christina Motta.

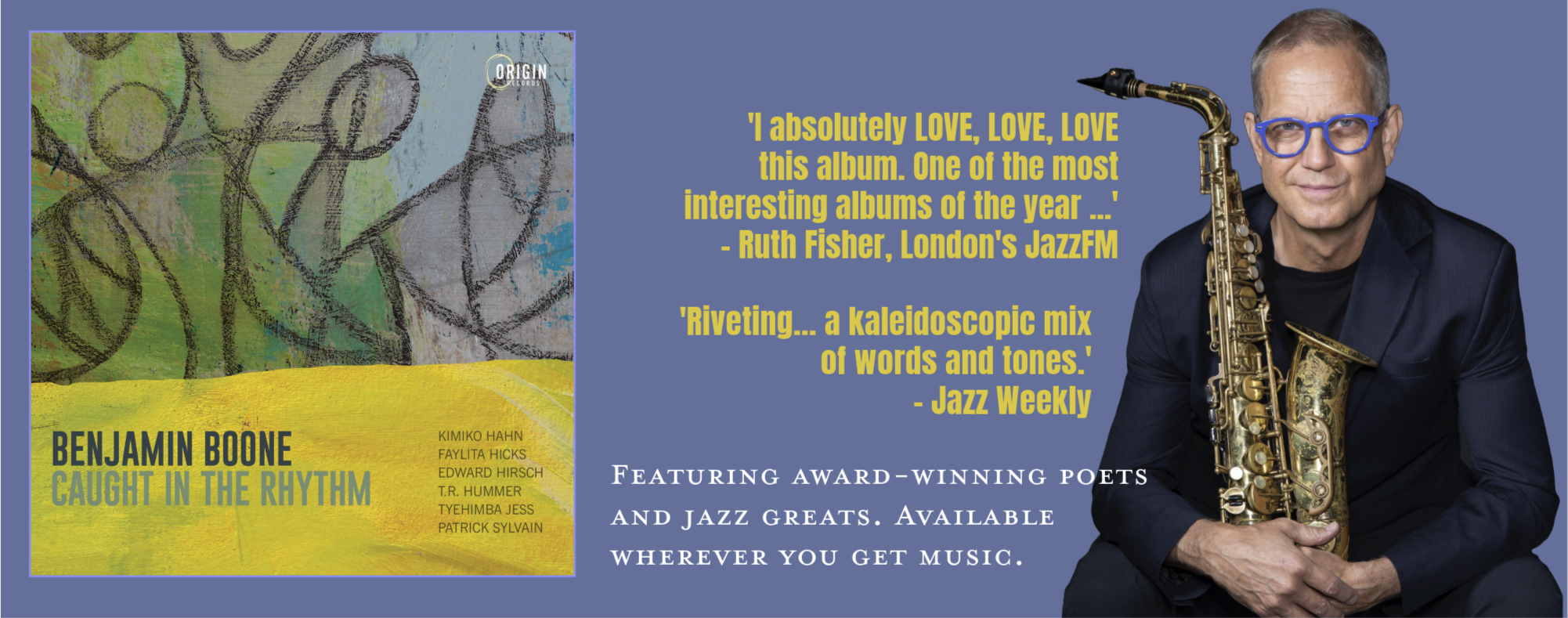

Former Fresno State music department office-mate Benjamin Boone remembers that Dr. Fortner once rolled out a scroll of a composition of his in the hallway. “It had to be at least 15 feet long,” Boone says. “Absolutely gorgeous handwritten music and illustrations. I had never seen anything like it.”

Dr. Fortner, who died June 25 at the age of 84 in Santos, Brazil, used that same artistry to handcraft his Orpheus programs with memorable themes. One that immediately comes to mind for me: a 2015 concert titled “The Old Curiosity Shop.” (Among the offerings: pianist Andreas Werz playing Erik Satie’s “Embryons desséchés (Dessicated Embryos),” which includes movements dedicated to sea cucumbers, lobsters and crustaceans with immobile eyes; and oboist Rachel Aldrich and members of the CSUF Composers Guild performing Mario LaVista’s “Marcias,” scored for oboe and eight tuned crystal goblets.)

Another: In 2018, he opted to package Clara Schumann’s birthday into a Mother’s Day concert (“She was the mother of eight children,” he cheerily informed me), then “invited” famous women composers from around the world to attend the party.

One thing you could expect from a Fortner-curated concert: variety. So much different music, so little time.

In my last in-person interview with him, in a 2018 episode of “The Munro Review on CMAC,” he talked about Orpheus and his wide range of interests.

“We can claim that in 40 years we have performed over 2,500 years of music,” he told me.

“Jack was wildly eclectic in his musical tastes,” says Claudia Shiuh, former principal violist of the Fresno Philharmonic and a member of Orpheus. “His enthusiasms ranged from Xenakis to rap to world music, from Wagner to Glass to Copland — all of which he brought to Fresno audiences through Orpheus, along with many other composers. He was a super-supporter of new music, both local and from far and wide.”

The Munro Review has no paywall but is financially supported by readers who believe in its non-profit mission of bringing professional arts journalism to the central San Joaquin Valley. You can help by signing up for a monthly recurring paid membership or make a one-time donation of as little as $3. All memberships and donations are tax-deductible.

Quick with a quip, clever with a program, sharp and hockey-tough with his students, dynamic with his audiences — Dr. Fortner exuded not just a passion for music but an insistence for it.

The acclaimed Mexican-American classical pianist Ana Cervantes, a close friend and collaborator who visited Fresno several times to perform with Orpheus, counted him as one of her favorite composers.

“Jack Fortner was a Protean figure of boundless musical energy, an artist of life, a man of great love and imagination, in addition to a teacher deeply respected and loved by his students,” Cervantes says. “For me, more than anything Jack was a tireless supporter of music, not just of new music; and in terms of programming, a curator who had few equals.”

☐ ☐ ☐

Jack Ronald Fortner was born July 2, 1935, in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

It gets cold there.

“The snow invited all the kids to play hockey in their backyards,” says his wife, Christina Motta, in an email from Brazil. He was a huge fan of the Detroit Red Wings. Dr. Fortner in his later years also bestowed his allegiance on the San Jose Sharks.

Not content to be just a spectator, he also played amateur hockey. And he played hard.

“He was a rough and tough hockey player,” says John S. Hord, who studied music composition with him at Fresno State. “Occasionally, he would walk into class with a new set of cuts and bruises to his face. I would say, ‘Did someone get out of line?’ He would respond, ‘Yeah. I had to take him into the boards.’ “

Yet that brawny swagger on the ice was balanced by a buoyant, exuberant personality off it, say two of the important women in his life.

“Never a dull moment with that one around, as anyone that has met him knows,” says daughter Lydia Fortner, of Fresno, who directs a historical Middle Eastern dance group, Banat Tanjora Ghawazee Bellydance, and once played in The Shroud, a Gothic rock band. “I always said he had lots of snap, crackle, and pop. He was noisy even when he was quiet!”

When Lydia’s son, Solon, was quite small, Dr. Fortner and Motta would have him over to visit, and one of their big games to play with their grandson was a form of dodgeball using a bucket of ping pong balls that had originally been used for one of Jack’s prepared piano pieces.

Motta, who married Dr. Fortner in 2008, says he was happy, kind and brilliant.

“Jack was the sunshine of my life, and it will be very difficult to live in a dark, gray world right now,” she says.

Top: Jack Fortner, left, in a photo from the 1950s. Below right: Fortner, center, as a member of the Modern Men jazz ensemble.

Growing up in Michigan, Dr. Fortner attended Catholic Central High School and Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, where he received his bachelor’s degree in music in 1959. There he met Phyllis Perry, his first wife, whom he married Aug. 13, 1960. They had Lydia in 1965.

In 1960 he began his study of composition in New York with Hall Overton of the Juilliard School of Music. He returned to his home state to receive a master’s degree in music in 1965 and Doctor of Musical Arts at the University of Michigan in 1968.

It was a busy time for the young couple. Phyllis was principal flutist for the Grand Rapids Symphony. Though jazz had been his original interest — at one point he toured the U.S. for a year playing saxophone in a band — his wife encouraged him to study classical music. Dr. Fortner also played flute, clarinet and bassoon, among other instruments.

He was prolific as a conductor, having served first as a star in his hometown — as the assistant conductor of the Grand Rapids Symphony from 1964 to 1965 and the conductor of the Contemporary Directions Ensemble at the University of Michigan from 1966 to 1970. He also did guest conducting stints at the Detroit Symphony and in Germany and Romania.

He took a job at Fresno State in 1970 and was music director of the Merced Symphony from 1971-77.

Teaching was always a strong suit.

“Perhaps my favorite memory is when I was in early grade school, he put me through his sight- singing textbooks that he was using in a class at CSUF,” Lydia Fortner says. “It almost felt like learning to unlock a code, absorbing all these proportions and relationships in music. As a result, my musical ear is still really good, even though I haven’t played an instrument in years. And it was fun to learn this magical lore from my amazing daddy.”

☐ ☐ ☐

Through it all, his musical world and tastes just kept expanding. He kept his students in the loop.

Hord, who went on to a career as a composer and a 25-year stint teaching at Fresno City College, recalls Dr. Fortner’s wide-ranging approach.

“Jack’s knowledge of the repertoire was vast,” he says. “Vast because it covered so many genres, time periods and instrument combinations. It was a special time studying under him. I would go in with a particular question or problem and he would prescribe — what else for a doctor to do — studying the scores to four or five pieces that seemed so unrelated at first. He was a walking thesaurus of instrument combinations.”

Jack Fortner was known for his wry wit.

For clarinetist Andrew Seigel, Dr. Fortner’s sense of humor was memorable.“I’m thankful for his description of me as a “more than just pencil-necked geek” in a (successful) recommendation letter for a Fulbright grant,” says Seigel, a professor of music at the State University of New York at Fredonia. “He was a good composition teacher, an inspiring musician, and a kind human being.”

When it came to Dr. Fortner’s interactions with students, Boone had a front-row seat.

In 2000, Boone had just moved from his job at University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and when he arrived on campus, he learned he would be sharing his office with Dr. Fortner.

“The small room was filled with various home-made instruments, stacked almost to the ceiling, including PVC pipes of varying lengths, file cabinets with scores stacked on top — the epitome of how a musical genius or mad scientist’s office/workshop/lab looks in the movies. There along the wall, in a break in the mayhem, was a desk — mine — yet to be cleared. Jack cleared it off, discussing the scores as he was removing them and placing them on one of the existing stacks. He asked about my favorite passages, then went to the piano to play them.”

Boone was slated to play saxophone on a piece written by Dr. Fortner for the final concert of the Orpheus season in May. That concert had to be canceled because of the COVID-19 crisis.

He will miss his former office-mate.

“Jack loved life, checking people in hockey, his wife Christina, Brazil, and music. Oh, how he loved music. And championing it. Especially new music. He understood it with a passion, and kept that passion alive for so long — or perhaps it was that passion that kept him alive for so long. With Jack, music and passion seemed one and the same.”

☐ ☐ ☐

His original interest in art and sculpting served him well as a composer.

Dr. Fortner treated his compositions almost as spatial creations, his daughter says. A big part of his approach had to do with how things were arranged on the page, and how they would be experienced by the performer just as much by the audience. Often there would be “bubbles” of musical sections on the page, to be played in no particular order, just as long as they all got played before moving on to the next ones.

“I have many memories of him cutting up score paper into long strips with just a few staves on them and taping them together into what seemed like yards-long strips, and working out the sequence of events on those,” she says. “For one piece he dropped grains of rice onto the staves and marked their locations, as a way to generate a dense texture of notes.”

At top: Grandson Solon Walker, Jack Fortner and daughter Lydia Fortner. Below, a family photo of Jack, Lydia and Phyllis Fortner, his first wife.

Recent works include “Windsong” for piano and wind quartet, described by Ana Cervantes as “a bewitching piece both mysterious and exciting”; and “Traces for orchestra,” which was premiered by the Orquestra Sinfónica de Campinas, Brazil in 2013 with the composer conducting.

He could make fascinating demands of musicians: In his 1977 “CHART for Jazz Band,” the solo saxophonist part is improvised to scenes from a film made by Dr. Fortner. In it he cut out pictures from comic books and glued them into a collage, grouped into sections that represent the style of famous saxophone players.

In 2014, I wrote for the Fresno Bee about Dr. Fortner’s “NOTHING and more,” which he preferred to call a sound sculpture rather than a musical composition. He knew he wanted to write an opera that had no meaning, at least in the verbal sense. So he invented three languages — one each for the baritone and mezzo-soprano vocal parts and one for when they sing together.

Male voice: Koo-wah Kohhoh dzah. Moh-sa-nee, moh-sah-ne.

Female voice: Shah-tay lee-lah-mah.

The piece was commissioned by the prestigious El Cimarrón Ensemble of Salzburg, Austria, which traveled to Fresno for the Orpheus premiere.

I asked him: Is this work “in six tableaux for six musicians” considered a quasi chamber opera? An English masque? A Greek drama? A fully staged theater piece? A multimedia sound sculpture?

He was comfortable with all those terms.

I recall trying to pin him down on the genre of the piece. He was a wily one when it came to questions that tried to make things tidy. His answer has always stuck with me.

“It is not experimental, because I do all my experimenting while I am composing,” he told me. “It is a finished product. Is it avant-garde? I don’t know. I am too close to the sounds and they sound normal to me. For sure, it doesn’t sound like Mozart or even Mahler, but is of its time. The listener must decide these things.”

☐ ☐ ☐

Dr. Fortner died in Santos, Brazil, a “very nice beach city” about 70 km from Sao Paolo, says his wife.

They met there in 1999. He had been invited by Gilberto Mendes, the composer and producer, to participate in a new-music festival. Dr. Fortner kept coming back. They married in 2008.

“We decided to share both countries — six months in the USA the other half of the year in Brazil — until 2014, when we moved definitively to Brazil to care for my mom, who was very ill,” Motta says. “But every year he returned to conduct Orpheus until 2019, his last performance.”

Along the way, Motta, a visual artist, created her own ties in Fresno. One of her artist friends was Aileen Imperatrice and her husband, Tony.

At top: David Fox, left, Christina Motta, Jack Fortner and Kathy Wosika. Fox and Wosika are strong supporters of Orpheus. Bottom right: Motta, Tony and Aileen Imperatrice and Fortner at an art exhibition in Fresno.

“I came to know Jack as a friend through a shared love of the arts,” Imperatrice says. “Tony and I attended some of his musical events, and he and Christina attended some of my art shows. Jack always had a laugh ready and created beautiful and intriguing music.”

One of those best times came in 2008, when Dr. Fortner’s “Fantasma” was performed by the Fresno Philharmonic under the baton of Theodore Kuchar. The full orchestra performed pieces by him two other times: the world premiere of “Prelude: The House of Atreus” in 1989; and “Symphonies” in 1999.

In the last years of his life while living in Brazil, his new music was a regular feature in Fresno. The Fresno Philharmonic’s music director, Rei Hotoda, performed Dr. Fortner’s piano piece “With the tip of your thought” in 2019 as part of its Proxima new-music chamber series.

His wife estimates he composed more than 20 pieces in Brazil. He also stayed busy conducting in Brazil and throughout Latin America, including the Festival Musica Nova Ensemble, Orquestra Municipal de Santos and others.

I ask Motta her favorite composition by her husband. She settles on the 2000 piece “Dark Music,” a sound sculpture for bass flute with live electronics, six percussion, piano, and alto saxophone.

Why?

“Because of the sound of bass flute that makes the atmosphere very dark and misty,” she says.

Before he died, Dr. Fortner was able to complete a final CD of his music. It’s been released in Brazil but hasn’t yet made it to the United States.

Doctors discovered Dr. Fortner’s cancer in January. He did not have a good reaction to chemotherapy, which damaged his liver and kidneys.

“The doctors just caught the cancer too late,” his wife says.

He was cremated on June 26.

His daughter is keeping plans flexible in terms of services in Fresno.

“When it’s safe to have gatherings of people again, I would love to have a celebration of life, and maybe even a memorial concert with members of Orpheus… but that will have to wait until the pandemic situation ends. For now, posts on social media will have to do.”

He is survived by his wife, Christina Motta, his daughter, Lydia Fortner, and his grandson, Solon Walker; and his nieces, Robin Siegel and Heidi Kubiak Jones, and their children.

Orpheus will continue without him, but it was already in the process of transition from a performing organization to a presenting organization after Dr. Fortner’s final concert in May, says board member David Fox. “We will be providing major support to the Philharmonic Proxima Concerts and to young groups such as the Tower Quartet via our donors and our annual fundraising house concert and dinner, whenever that can resume, he says.

Dr. Fortner bids adieu at the Fresno airport.

For me, it’s strange to think that I won’t be receiving any more emails from Dr. Fortner extolling the virtues of such-and-such young musician or asking for coverage of some concert with an offbeat theme.

Terry Lewis knows how I feel.

“I can’t believe Jack is gone,” says the noted Fresno actor and singer, who heads the music and media department at Fresno State’s Madden Library.

“I just talked to him last month about locating a specific score in his donated papers, because someone in Brazil wanted to play it,” Lewis says. “I told him it might be a while before we could access his papers, and he said not to worry, that it wasn’t a rush — and a month later he was gone. I will miss his zest and enthusiasm. He was the Energizer Bunny of the contemporary music scene in town. A long, full life, but, still, what a loss.”

DAVID FOX

Great article Donald. Jack would be pleased. He might say it covers the waterfront like Brando.